The logic is so simple, it’s almost circular: before someone buys from you, they must know about you.

Here enters the metric known as “brand awareness,” something marketers everywhere are striving towards and at which every CFO is rolling their eyes.

In ecommerce, where it is often difficult to truly differentiate purely on product features, we often have to fight for mind share and an emotional connection.

Why, after all, does one choose a Casper mattress over a Purple mattress but for branding?

The question, though, is how do we actually measure brand awareness? Hint: there are many different, sometimes conflicting methods.

Additionally, can we correlate brand awareness campaigns to actual dollar sign business goals?

We’re going to help you try to answer those questions here. First, let’s get a grasp on the terminology so we’re on the same page.

What is Brand Awareness, Anyway?

Brand awareness is “a measure of a brand’s relative cognitive representation in a given category in relation to its competitors.’

In essence, it is a quantitative measure of how well your brand is known by your target market.

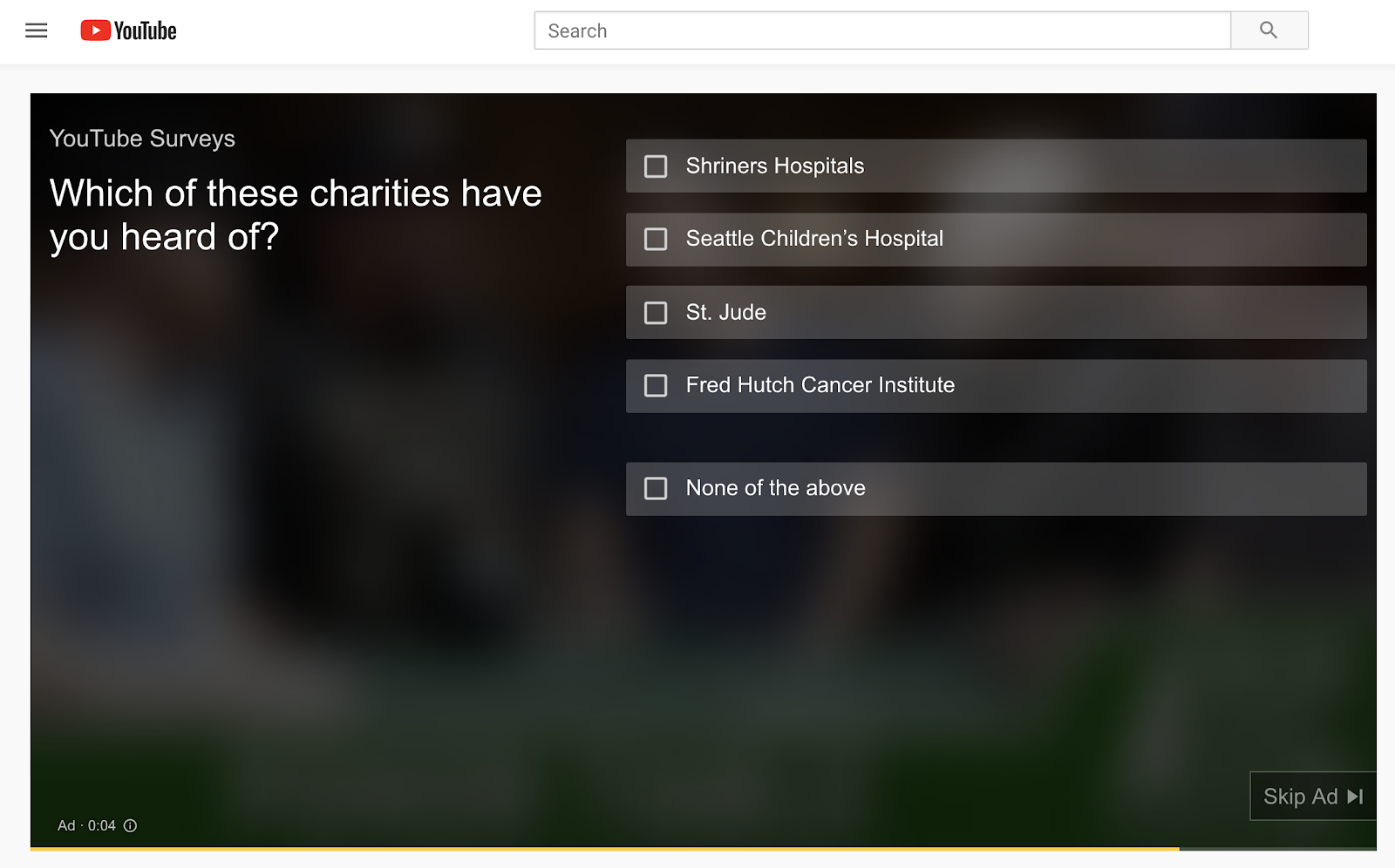

The typical academic methodology used is the “brand recall survey,” in which a group of consumers are asked to name as many brands as they can in a given product category (say, live chat software). If they recall your brand at higher rates than others in that category, you have good brand awareness.

Brand awareness is sometimes confused with other brand metrics such as brand equity—the overall value of a brand and its assets—or brand loyalty—the extent to which your customers would stay with you in the presence of competing offers.

Synonyms of brand awareness are mind share and share of voice.

We can really put this into concrete terms when we think of a specific ecommerce product category; let’s say direct to consumer tea sellers. If you were to ask a sample of people shopping for tea which tea brands they could remember, a hypothetical break-down could be that 55% knew The Republic of Tea, 40% knew Teavana, and 25% knew Pique Tea.

However, things get more complicated when you begin to ask questions about the methodology.

How many people do we need to ask? Which people? What if we expanded our product category to “health drinks,” or even just “beverages?” Then Pique Tea is suddenly competing in the same category as Kombucha or Coca-Cola, respectively, which just doesn’t seem right.

These are complicated questions, but there is a short answer: brand awareness as a metric should track as narrowly as possible against your target market. Everything else is noise. Your findings should be actionable, and you should be able to track them over time and against competitors.

As you’ll see below, there are many methods marketers currently use to track brand awareness. I’ll outline them and we can judge them based on the above criteria.

5 Ways to Measure Brand Awareness

I’ll be focusing only on four of the most common ways for online retailers to measure brand awareness as well as one new way I believe is more effective.

1. Brand Recall Surveys

The most common way to measure brand awareness is by selecting a representative sample of consumers in your target market and asking them which brands they can recall in your market category.

Within this method, there are actually a few different flavors of brand awareness measures: top of mind, spontaneous, and aided.

Top of mind is when you give someone a product category cue, and you’re only interested in the first brand they say. Spontaneous awareness is simply measuring how many brands one can name without any assistance. Aided awareness is more of a recognition measure that measures how many people recognize your brand name when prompted about it.

Taking into account all of these survey approaches and despite being the most common and the most formalized and studied, I still believe brand awareness surveys may be the least useful method of any on our list. At least for the vast majority of businesses, especially those digitally-native ecommerce sites.

Basically, many brands will either cluster near the top or the bottom of a chart in terms of their salience.

At the bottom of the chart, where the vast majority of brands actually reside, there is massive variance in the brand awareness metric. This leads to low predictive validity (meaning you can’t really take action on this metric) and questionable longitudinal validity (if variance is high the second or third time you measure it, what looks like a positive or negative change might just be measurement error).

For larger consumer brands like Away or Quip, this might be a great method.

For smaller consumer brands like Winc and Chameleon cold brew coffee, your sampling needs to be much more rigorous in order to make it useful.

For most B2B brands, like BounceX or Ahrefs, surveys like these are pretty much useless.

2. Direct Traffic

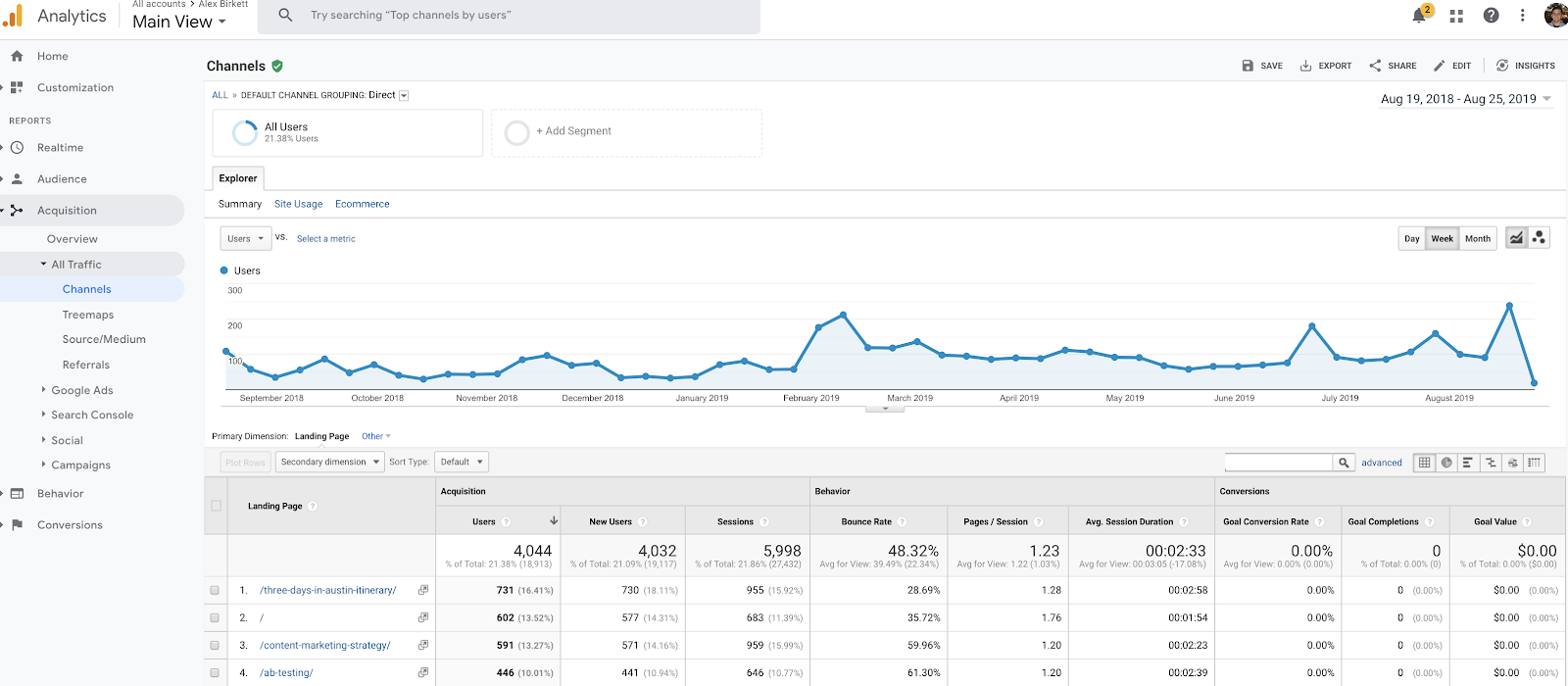

Direct traffic is one of the easiest, yet least rigorous ways of tracking brand awareness. It’s really not a bad metric to keep an eye on. It just doesn’t really track what we’ve defined as “brand awareness.”

Acquisition > Channels > Direct

The big problem with direct traffic: it’s very inaccurate as an attribution channel.

If you’re using Google Analytics, know that many other channels are accidentally bucketed into “direct,” especially if you don’t follow UTM tagging best practices. For instance, what you think of as direct traffic might just be email or social traffic that has been bucketed as direct.

A second problem: direct traffic may come as the result of many things, including but not limited to:

- Public relations events (ex. fundraising)

- An increase in customers logging on to contact with customer support or return items.

- Your own staff working on your site

- Not properly installing your analytics code inside of your ecommerce platform

So, it’s not very narrowly defined, which is problematic only if we’re looking at this as an accurate construct in itself. If we’re looking at it as a directional and indicative measure, especially in relation to competitors, it’s not a bad thing.

“A huge portion of our direct traffic comes from people reaching our homepage just to log into the app,” says Mark Lindquist, marketing strategist at Mailshake.

“We have to be careful about removing app user traffic from our general traffic numbers for that reason. Otherwise, we’ll see consistent growth in direct traffic, but it’s from our consistent growth in customers, not from brand awareness or any directly attributable marketing campaign.”

This isn’t a bad thing, obviously, so keep an eye on direct traffic. Just don’t call it “brand awareness.”

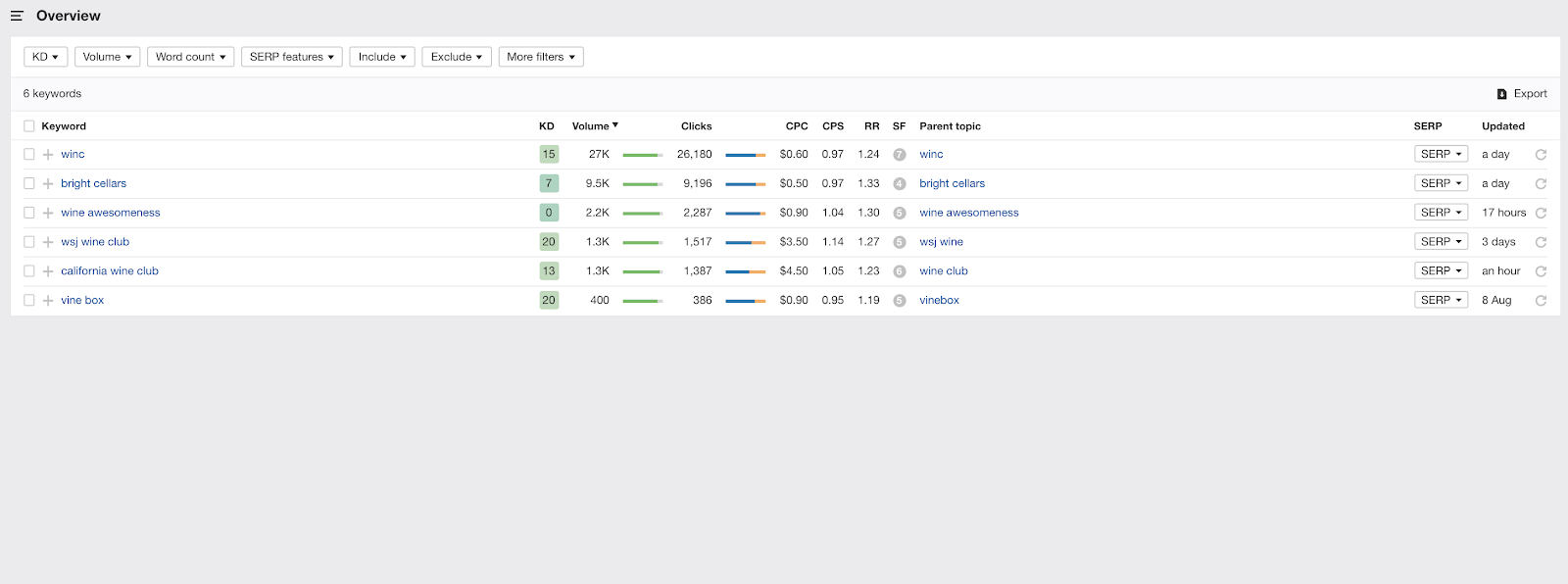

3. Branded Search Traffic

Branded search traffic is one of my favorite ways to audit brand awareness, especially for competitive research purposes. This is a great metric for ecommerce sites that operate primarily online, though even those with locations may be able to tie some branded search back to brand awareness efforts.

This metric, again, suffers from its unrigorous scoping; someone may search your brand for many reasons, from general curiosity to public relation events to customer service inquiries and more.

Additionally, most search data is at best a directional estimate, which means you’ll never get a truly precise number here.

Branded search benefits, however, in its directionality and the ability to compare with competitors. Unlike direct traffic date, you can actually see what your branded search is in relation to others in your industry. Simply plug your brand and a few other competitors into Ahrefs and check out the numbers.

If you’re using this as a brand awareness metric, there are two things to know:

- It’s not incredibly actionable. You can’t make any near-term decisions based on this brand awareness measure (though it can help with your positioning).

- It’s most useful if you track it over time and in relation to competitors. Your number should be growing in relation to your competitors over time, and you can use this metric to help you prepare sales enablement materials, such as competitor feature comparisons (example from HubSpot here).

4. Social Media Mentions

I’ll give away my bias up front here: I don’t think social media mentions is a viable brand awareness metric, no matter how you slice it.

It doesn’t measure what we think of as brand awareness—neither in the sense that it measures people who are aware of your brand nor that it measures people in your target market. I believe no one should consider mentions or impressions on social in any way a reputable brand awareness measure.

First off, context matters. If you launched a great new product, you might get a spike in social mentions and impressions. You may also get a spike if your CEO was involved in a scandal. Maybe you just started posting memes and they’re really getting some traction…but with a totally irrelevant consumer segment.

Even if you tie in sentiment analysis, I still think social media mentions or impressions are a weak measure of brand awareness. That’s not to say social media is a useless activity; clearly that’s not true, as some brands have built their businesses on Instagram or Pinterest. Just don’t call social media impressions “brand awareness.”

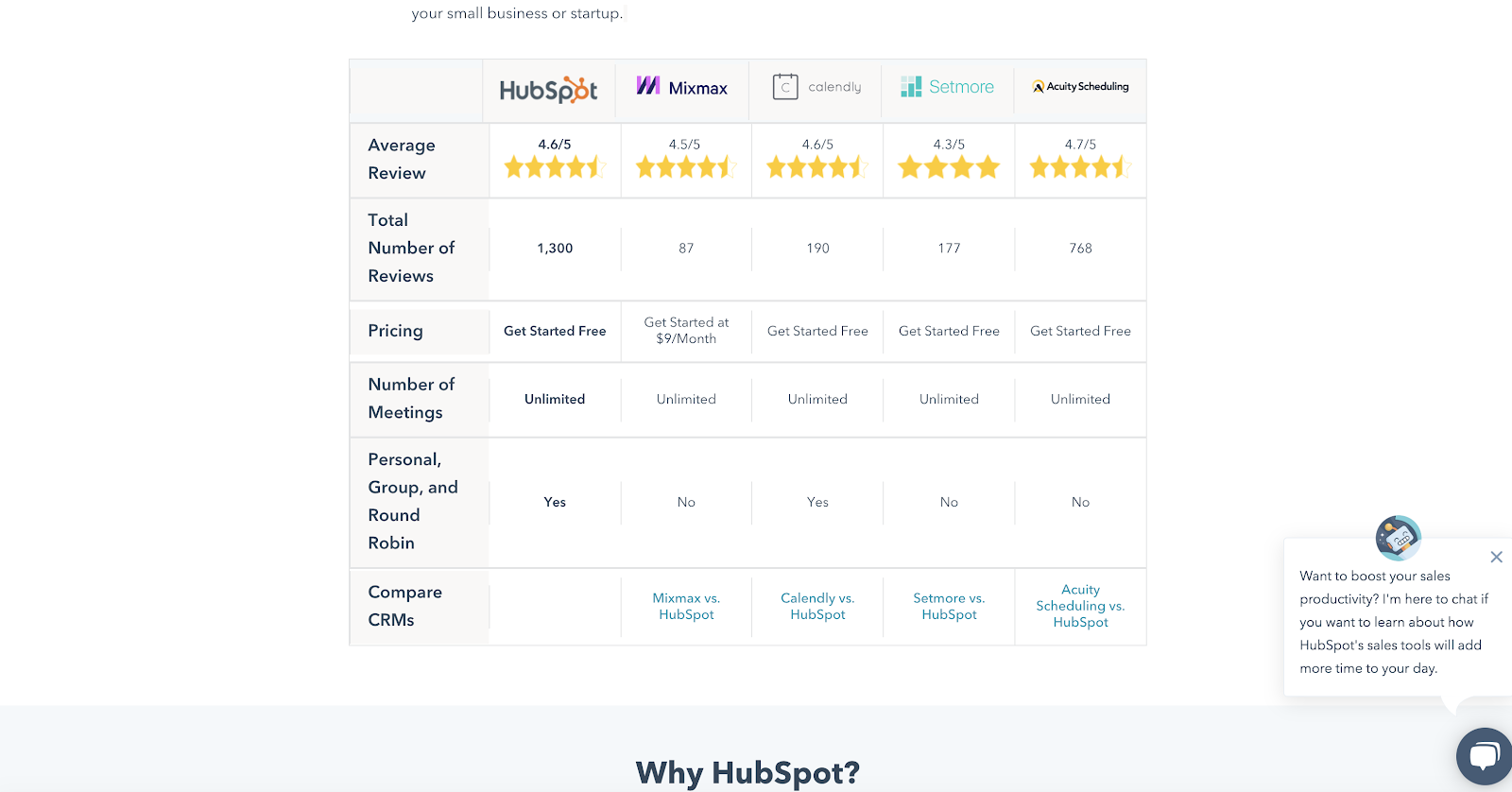

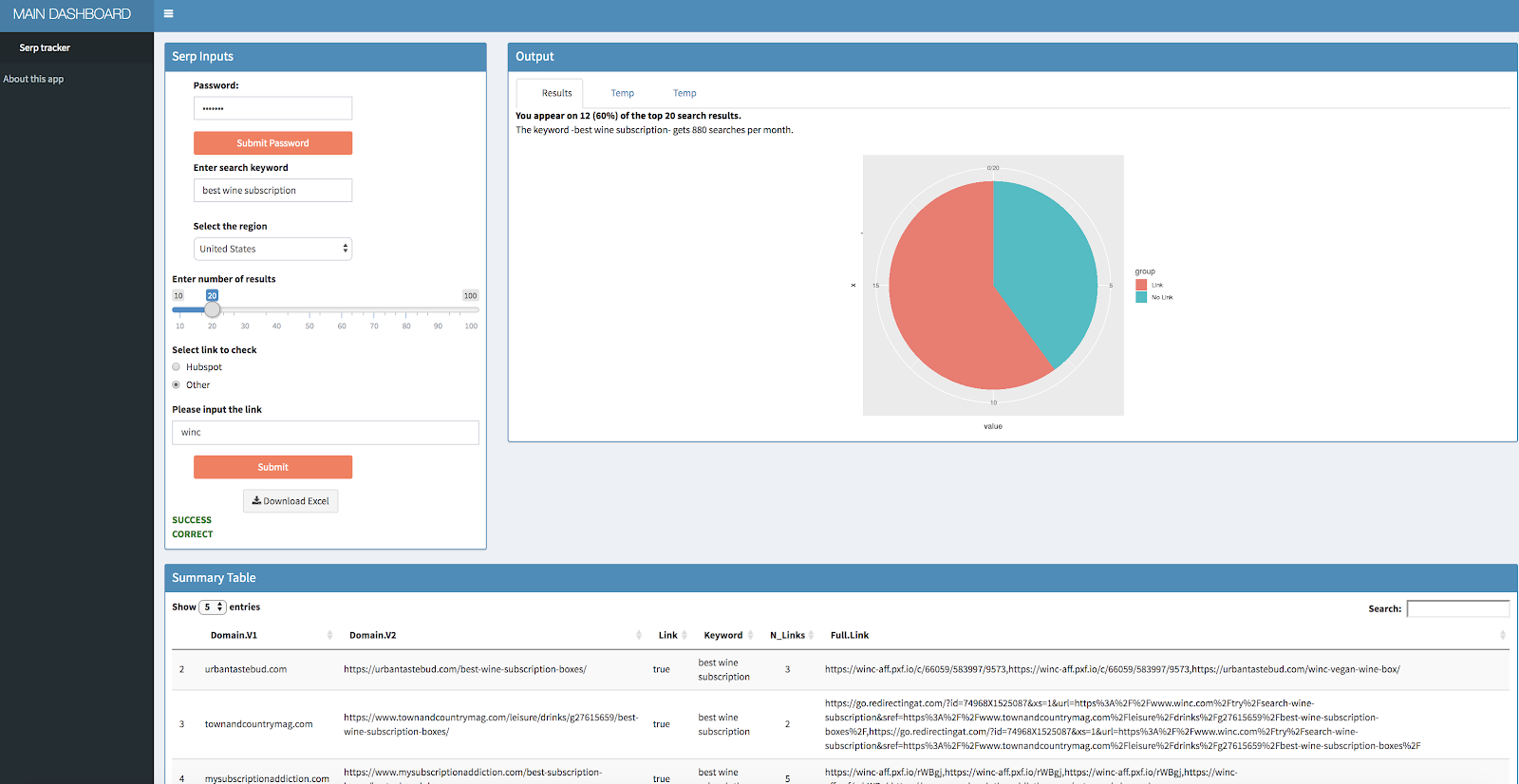

5. SERP Real Estate

Digitally-native businesses should probably care about SEO as an acquisition channel, but I’ve proposed a way to use search as a brand awareness measure as well.

You can probably define your market segmentation or category in terms of a search keyword. For example, Winc is a “wine subscription box.” Quip is a “toothbrush.” Kettle and Fire sells “bone broth.”

As it turns out, many (many!) consumers turn to Google to discover new products in known categories or to do research and get opinions on the best product to buy. These search queries look like this:

- “Best wine subscriptions”

- “Best toothbrush brands”

- “Best bone broth brands”

In almost every product category I’ve seen, these terms have both high search volume (lots of people are searching) and high intent (the people who are searching are looking to buy). This makes it a red hot bullseye arena for you to identify those truly in your target market.

If your brand isn’t to be found in these search terms, you’re not a part of the conversation, and therefore you won’t be considered when potential customers are searching.

So what’s the metric? Look at the top 2-5 pages of Google for your product category search term, and count how many of the pages mention your product. You can do this manually or you can do it by using a scraper like SEO Quake and analyzing the outlinks in Screaming Frog.

This is such a powerful metric that I built a tool in R so we could easily do this for any product category keywords:

Okay, So Does Brand Awareness Matter for Ecommerce?

Brand awareness is of obvious importance to online retailers. In fact, brand equity—of which brand awareness is a part—may be one of the only true moats for many digitally-native ecommerce brands.

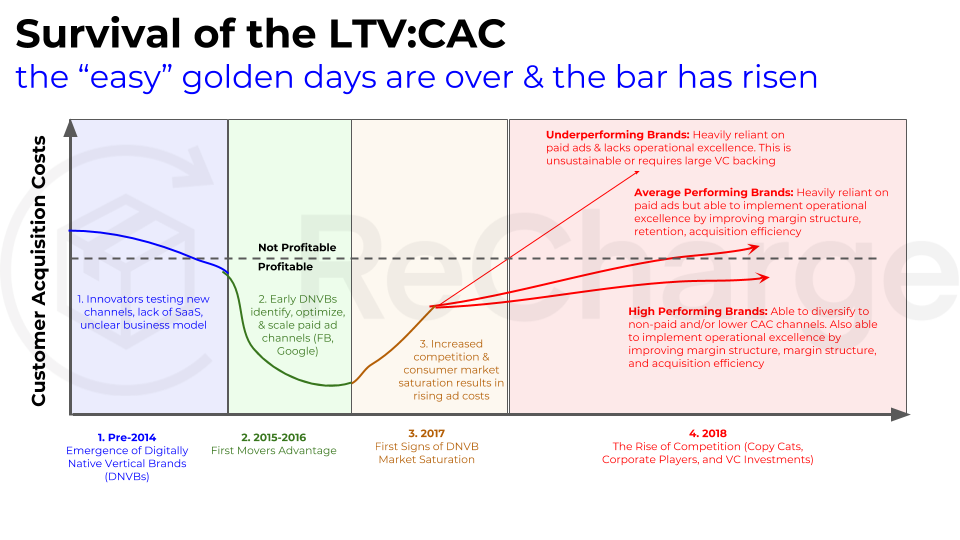

As Wilson Hung recently pointed out, the golden era of DTC brands may be coming to an end. In the early days, brands were able to take advantage of decreased costs of both starting their store and scaling via paid channels.

Now, however, competition has driven ad costs up and has made it more difficult than ever to differentiate on product alone.

As I’ve mentioned before, if there is a meaningful difference between a Purple, Casper, and Tuft & Needle mattress, I’m not sure what it is (and I don’t think most consumers could tell you either).

Two Ways to Build Out Your Ecommerce Brand In 2019

This rise in CAC (customer acquisition costs) leads to a logical conclusion for brands. We can focus on two things:

- Decreasing acquisition costs

- Increasing lifetime value

If I had to guess, I’d say decreasing acquisition costs will come from two primary means:

- The diversification of customer acquisition channels

- A decidedly “traditional” advertising approach for the market leaders

As for the latter, those first movers who have carved out a large customer base for themselves already may be able to double down on paid advertising and branch out to traditional media buying as opposed to simply relying on performance and direct response. This could include offline media like television, radio, and billboards, and it could also include partnerships, sponsorships, and influencer work.

Brand salience becomes an effective differentiator at the margins. In other words, if you can spend enough money and time to make it that people think “Purple equals high quality mattresses,” that’s a big emotional moat other brands will have difficulty crossing.

This, however, is a terrible approach for upstarts. If you’re a newer, scrappier competitor, you’ll almost certainly have to diversify your approach to customer acquisition. This may include non-paid channels like content marketing, SEO, social media, or influencer marketing.

Large brands will also probably branch out to non-paid channels with time as well.

The final consideration for ecommerce brands looking to stand out in 2019 and beyond is to build out a world class retention program, thus boosting LTV.

This includes the simple, low-hanging fruit like failed payment recovery, and it also includes the broader initiative of doubling down on customer service and improving the customer experience at every step of the journey.

After all, it’s 2019, and no one trusts marketers. We trust our friends, though. And I bet if you looked at your last 10+ online purchases, most of them would be driven by word of mouth.

Conclusion

Brand awareness as a concept is clearly important to ecommerce brands. In fact, brand equity may be one of the moats winning companies compete on in the coming years, now that competition and customer acquisition costs have risen precipitously.

I’d caution against using some of the above metrics as an actual quantitative measure of brand awareness, however. Many of the common metrics don’t actually measure brand awareness at all and are simply emergent properties of many other functions. The two that work well—brand recall surveys and SERP Real Estate—mostly tend to be effective for larger, better-known brands.

My suggestion: Build your acquisition strategy out like you would an investment portfolio. Keep 80% of it for directly attributable, conversion-driving activities, and leave 20% open as brand equity-building activities. That way, you capture most of the upside of the persuasive aspects of brand building, while never losing out to more data-driven competitors.